NASA recently confirmed that there are over 5,000 exoplanets and the rise in numbers is not expected to slow down. As technology improves, it allows us to look even further into space. So far, all the stars found have at least one planet. Considering the number of stars in the galaxy, it follows that there are a lot of exoplanets still to be discovered.

Exoplanets range in size from two times bigger than the Moon to 30 times bigger than Jupiter. Most of these exoplanets orbit a star, though there are both rogue exoplanets that do not orbit stars and exoplanets that orbit twin stars.

Exoplanets are interesting in and of themselves, in that they can teach us more about the universe, just like the planets in our own Solar System have done. But the exoplanets in the habitable zone are especially interesting for us to look at.

Is The Habitable Zone Habitable?

The habitable zone is defined as the zone around a star where water can be present in a liquid form, so the habitable zone is not necessarily habitable for us; we shouldn’t expect to set up our second home on one of these exoplanets.

What lies in the word habitable is the fact that scientists generally agree that life cannot exist without water, so for an exoplanet to potentially have life, it must have or have had water. The habitable zone is therefore the zone in which we believe the first requirement for life could be or has been present.

An exoplanet in the habitable zone is not guaranteed to have all the requirements we believe are necessary for life, though. We know, from our own Solar System, that a large gas planet like Jupiter is far less likely to have habitable conditions. Finding the exoplanets in the habitable zone is only the first step. Next, we roughly sort through those to see which ones warrant a closer look.

Fine. This Exoplanet Is in The Habitable Zone. Now What?

Once an exoplanet is determined to be in the habitable zone, other kinds of data are examined. As mentioned in the section above, we know from our own Solar System, that gaseous planets do not offer the best conditions for life.

In fact, there are four different types of exoplanets that scientists have agreed upon:

Terrestrial exoplanets are defined as being rocky worlds that are the size of Earth or smaller, while super-Earths are rocky worlds that are at least twice the size of Earth. These are the planet types that are most interesting to look at within the habitable zone, as we believe these pose the best potential to offer habitable conditions, including a suitable atmosphere.

Another important condition is the kind of stars the exoplanets orbit. There are many different classifications of stars, and some stars are more active. Imagine a terrestrial exoplanet placed perfectly within its star’s habitable zone. If the star is very active and prone to erupting in large flares, those flares might reach the exoplanet and completely sterilize it, killing off all life before it has a chance to evolve. Since one of the conditions counteracts the others, this means that all the other conditions are irrelevant in this case.

Recommended Reading

To sum up, all these conditions must be met for an exoplanet to have the possibility of what we know to be life. Yet, even if we find an exoplanet that perfectly lives up to all the requirements, it will be very far away. In fact, most of the exoplanets we have found so far, are hundreds or thousands of light-years away.

So, When Will We Find Life on an Exoplanet?

The short answer is, not for a very long time. Due to the distance to most of the exoplanets discovered so far, we are unable to reach them at present. It will be a very long time before we can send a rover to one of those planets, as we did with Mars. But that doesn’t mean we cannot look for signs of life.

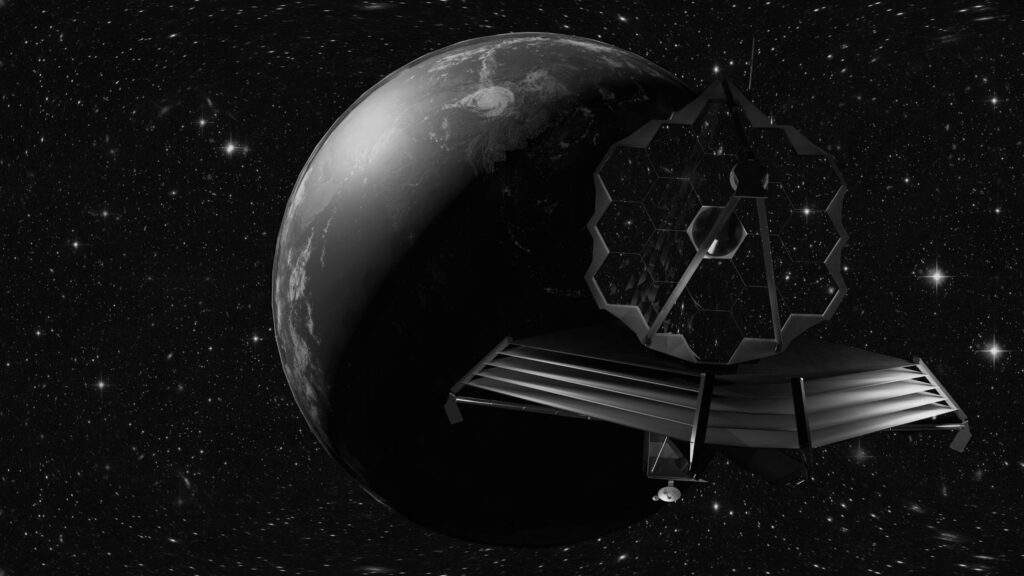

The Kepler Telescope made a giant contribution towards finding and confirming new exoplanets, and the hope is that the recently launched James Webb Telescope will do the same.

Even if we aren’t able to gather samples from exoplanets in the near future, there are other ways to establish the possibility of life on them. The telescopes can look for atmospheres, (though these are difficult to detect at present), technosignatures, or traces of technology (like smog on our own planet).

The James Webb Telescope certainly won’t be the last of its kind that we launch into space and, with our ever-developing technology, the possibilities of discovering life or traces of life on an exoplanet are ever-increasing.